#26: The downside of keeping your identity small

You'll feel congenitally misunderstood and never commit to anything worth doing

I’ve always been a proponent of keeping one’s identity small. Reading Paul Graham’s essay several years ago articulated a belief I’ve always held: the more identities you hold, the dumber they make you.

Identifying with things prevents you from seeing some parts of reality—the parts relevant to those things—clearly.

British conservatives can only tolerate so much conversation about the ills of empire and colonialism. Eton or Phillips Exeter alums aren’t especially open to arguments against private schools. Bitcoin maxis aren’t the most lucid about the future of the monetary system. You get the idea.

There is a spectrum between being totally noncommittal towards an identity label, and being totally committed to it. At one end lies dilettantism. At the other extreme lies religion.

I’m realising that in my effort to stay clear-headed about reality, I have avoided committing to things I want to keep doing, to who I want to be.

I’ve always been uncomfortable when people use a coherent identity category to introduce me.

When I used to get introduced as a “physicist” I felt a pang of anxiety. Don’t they know I’m more socially competent than the average physicist?

More recently I get introduced as a “marketer”, which causes a flash of annoyance. Don’t they know I’m smarter than the average marketer?

Now my job title is “head of special projects” and I’m embarrassed by both the grandiosity and imprecision of that label.

You can learn a lot about who you are from the ways people introduce you. But all introductions I’ve ever had feel hopelessly sparse. Like a 1-D silhouette of a high dimensional hypercube. These conventional intros convey only a vanishingly small fraction of who I feel I am.

How do you get people to introduce you in a way that feels true to yourself? And what do these introductions have to do with who you really are?

I’m not “a marketer”, I tell myself. Sometimes I “do marketing”. I’m not a “physicist”, but I did “study physics”, and even did “physics research”. I’m not a “writer”, but I “like to write”.

I’ve been cringing against identity labels for years.

Until recently, I was convinced I resisted these labels to preserve my intellectual independence. That keeping my identity small was a mark of my virtuosity. But now I know I was mistaken.

I rejected identity labels because I was too scared to make a commitment about who I am and who I want to be.

In Atomic Habits, James Clear talks about how, if you really want to adopt a new habit, you have to make it part of your identity—weave it into the very fibre of your being.

Saying “I go running 3 times a week” is one thing. It’s a statement you may or may not live up to. But saying “I am a runner” almost guarantees you’ll go running 3 times a week. Once you give yourself a name, you feel you have to live up to it.

Once something becomes part of your identity, you’ll try to live up to it, but you’ll become dumber about it too. In-group members often reject useful truths, especially those presented by outsiders, in order to defend their tribal identities. “Running is terrible for your joints” say the gym bros. “Our VO2 max levels are much higher than yours” reply the runners. Both are right; neither are listening.

Keeping your identity small keeps you smart about the world and it keeps you free to choose what you want to commit to. But, unless you want to be a dilettante forever, you have to commit to something.

And in committing to something you traverse the path from dilettantism towards religion. Everyone who gets real things done has delusional beliefs (about the importance of their work, their own competence, etc). But at least you can choose what you’re delusional about.

Keeping your identity small keeps you smart but passive. You can see the world for what it is, but make no commitments to affect it.

Enlarging your identity makes you dumber along certain dimensions, but more agentic along them too. Committing to an identity is scary, but once you do, it’s a downhill battle to do the activities that maintain that identity.

Said another way: “Growing Up” is just deciding which Type of Guy you want to be.

Identity categories are combinatorial, so there are infinitely many Types of Guy out there. You do have to choose, but your choice is not final. Identities change over time.

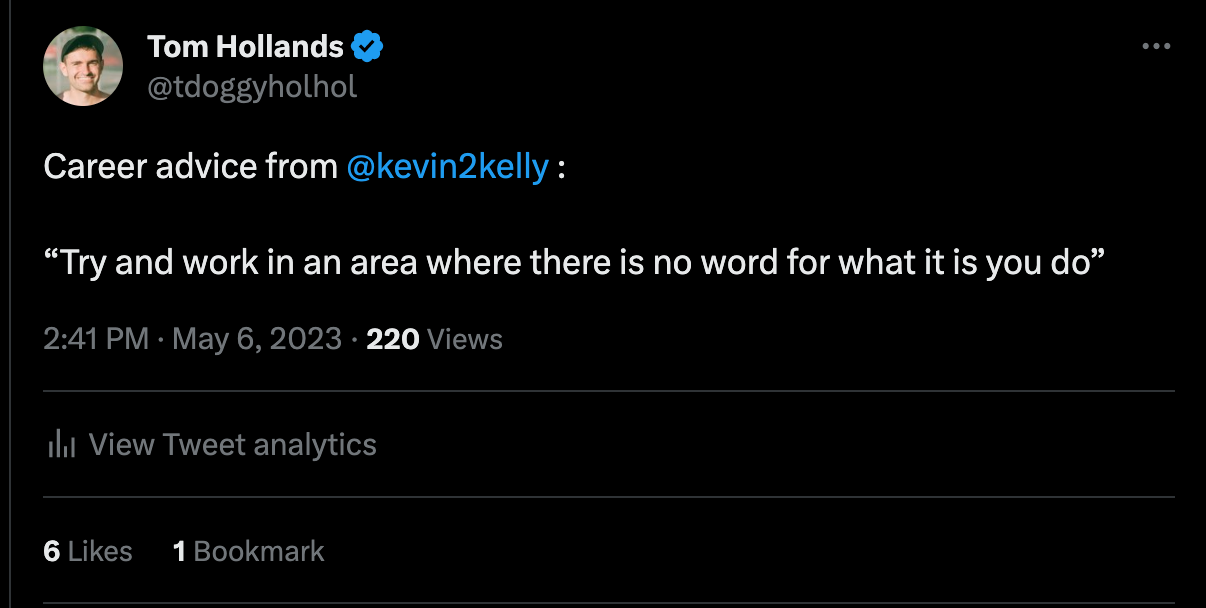

In the end, you should follow the Visakanv advice of “focusing your attention on what you want to see more of.”. Instead of relying on other people to articulate who you are, you can create the identity category you want for yourself.

The more you practice telling people what you’re spending time on and who you want to become, the better they’ll introduce you to others. Their introductions will be more in line with who you feel you are.

Trying out identity categories is kind of exhilarating, like writing your own Pokemon card:

I am a quantitative growth marketer and strategic project manager.

I am a business-scientist and a systems thinker.

I am either a strong businessperson with technical inclinations, or a weak technical person with a business inclinations.

I am a relatively charming physicist, and a relatively physics-y salesman.

I am a curious writer trying to understand the world.

I am an armchair philosopher, anthropologist, mathematician, and investment analyst.

I am British by birth, Third Culture Kid by necessity, and I’m becoming Canadian by choice.

I am a lager drinker, sushi eater, mogul skier, newsletter writer, touch rugby community leader, startup operator, cold e-mail sender.

I am a runner, a skier, a climber, and a touch rugby player.

I am a writer, a thinker, a scientist, an athlete, a loving partner, and a caring friend.

Committing to an identity requires courage. Telling people who you are and who you want to be requires vulnerability. But both are better than not committing to anything at all.